Artistic Processes & Preoccupations

Whatever has the power to draw the eye, for reasons sufficient to the artist, is art.

Carwheel, Pont des Arts, Paris France, 1998

b.1998.1

The first of Martin Firrell’s works created expressly for public space was performative; a cartwheel across the Pont des Arts in Paris France

(1998.1).

The performance was carefully planned in advance and photographed for posterity by the artist's friend, Russian concert pianist Yekaterina Lebedeva, using a 35mm b&w disposable camera.

The first of the artist's print works for the public realm was a series of 14 postcards, 148mm x 104mm, printed on various stocks. 13 cards display text where an image would more usually appear on a picture postcard. The 14th card shows the artist's cartwheel on the Pont des Arts.

Aimless Afternoons, Glasses of Kir, 1998

1998.2

The postcard texts were intended to take on a public life of their own as they passed through the postal system. Once they reached the recipient, a card might be displayed on a mantelpiece or similar and in this way it would have a second ‘public presence’ in the domestic sphere.

Considered collectively, the postcard texts explore the possibility of being more deeply implicated in the lives of others or as the artist put it, 'I wanted to ask if it were possible to operate at a level deeper than friendship alone, to find interactions that challenged the conventions of mere sociability and offered new depths of value and meaning.'

The text of postcard 10 describes the evocative nature of the paper detritus of everyday life - things like restaurant bills and dry-cleaning tickets - items that unintentionally constitute a biography-in-litter of the lives we have lived:

Aimless afternoons, glasses of kir, early dusk, remembered sentences, telephone calls, cloakroom tickets, restaurant bills and train tickets, telephone messages, folded receipts. And the sudden victory, the sudden opening out of feeling.

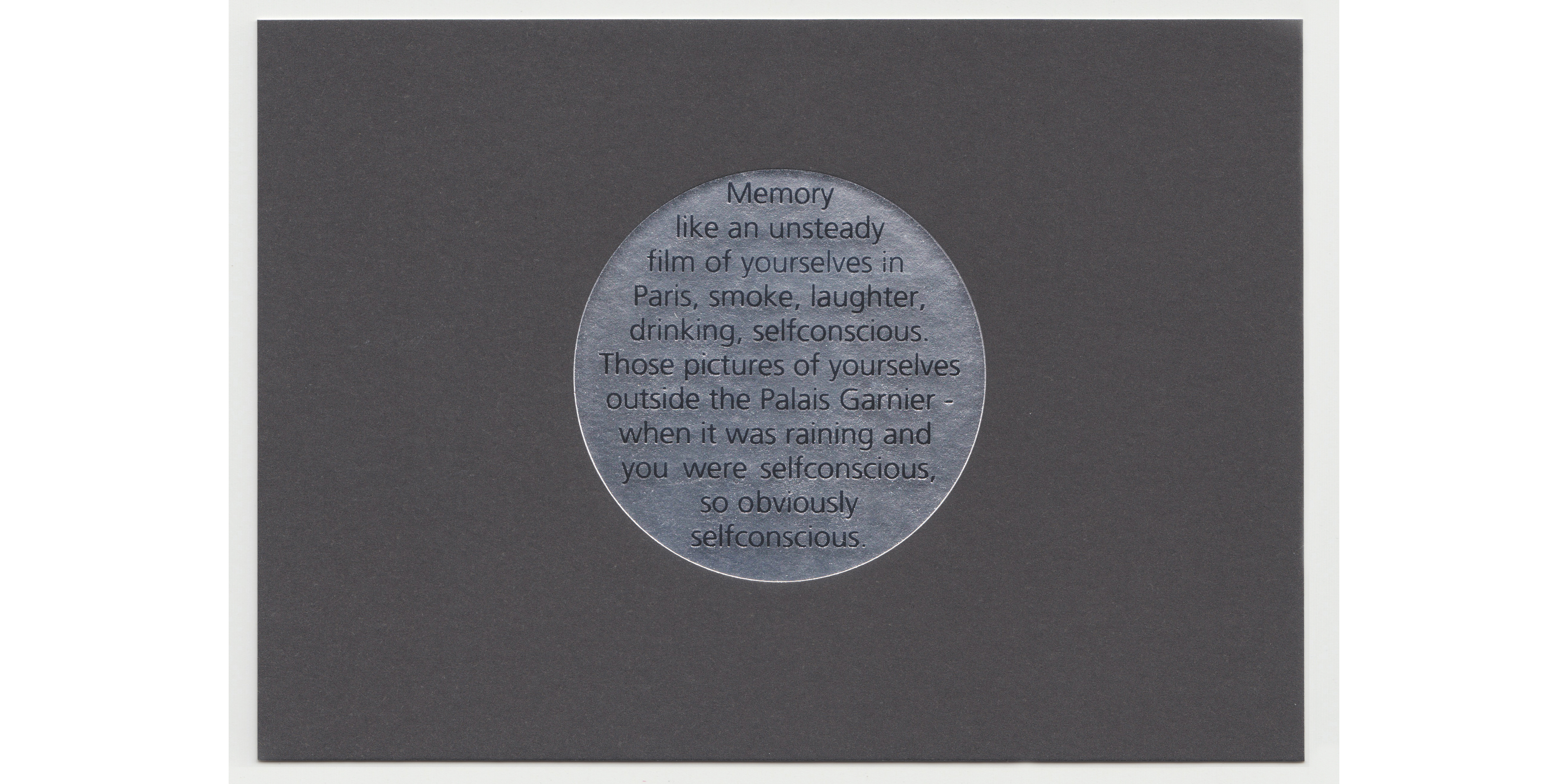

Postcard 12 evokes the power of a photograph to revivify a moment in time:

Memory like an unsteady film of yourselves in Paris, smoke, laughter, drinking, selfconscious. Those pictures of yourselves outside the Palais Garnier when it was raining and you were selfconscious, so obviously selfconscious.

Memory Like an Unsteady Film, 1998

1998.2a

The artist explained: ‘In Paris, we had our photograph taken on the steps of the old Opera Garnier - a ludicrously over-priced polaroid picture was presented to us stuck into a thin card folder with a crude illustration of the Eiffel Tower on the front. This photographer-of-tourists made us uncomfortable for some reason and the poor quality of the polaroid taken in low light made the picture seem awkward, lost, a fragment from another time.'

Martin Firrell and Yekaterina Lebedeva, Opera Garnier, Paris France, 1998.

b1998.5

The postcard series was followed by 3 fly-posters for London’s Soho:

Untitled (Fly-posters),

(2001.1.1 - 2001.1.3).

These are the first of the artist’s works in poster form. The language of these artworks is heavily influenced by the French novelist Marguerite Duras.

NOTE

Marguerite Germaine Marie Donnadieu (1914 – 1996) known as Marguerite Duras, French novelist, playwright, screenwriter, essayist, and experimental filmmaker; winner of the Prix Goncourt in 1984.

Duras achieves an astonishing intensity of feeling using very few words, usually repeated with small variations in word order or tense. Whereas the sentence constructions of literary French tend to be complex and labyrinthine, Duras deploys a simple, reduced language in order to be as clear and compelling as possible. This undecorated directness is a source of immense expressive power.

Then That Other Thing Happens, 2001

2001.1.1

Many contemporary artists use language to confound and disorientate the viewer; the influence of Duras leads Firrell to a pared and direct language, which can be readily understood by the vast majority of people. Language deployed in this way supports the artist's efforts to ‘make the world more humane’ (artist’s own words).

The fly-posters convey intensity of experience with sensorially overloaded language, presented on foiled stocks that gleam gold, silver and copper against Soho’s grubby walls.

Location forms an integral part of the artwork

Never Fall for Someone with a Body To Diet For

(2001.4.2).

On the corner of London’s Leicester Square, just a short walk from the gay district of Soho, the artwork speaks to body shaming and unrealistic expectations of male beauty often found in the gay community at the time.

Never Fall for Someone with a Body To Diet For, 2001

2001.4.2

This location specificity is unusual and the majority of the artist’s billboard artworks appeared digitally across the country, occupying unsold space, appearing wherever that space became available and alternating with paid-for advertising for everything from training shoes to cola drinks.

This proximity to big brands confers an ironic legitimacy on these artworks in the eyes of the general public. When an artwork occupies the same space as objects of desire like Levi’s jeans or Nike trainers, it is inferred that it shares their stature as media objects.

In many ways, Firrell's billboard artworks can be regarded as repurposing the existing digital billboard display system. Firrell has also experimented with repurposing other systems, for example, the EPOS system at Border’s Books. In 2004, he added public art messages about the societal importance of contemporary writing to every Borders' till receipt.

Paula, Michael and Bob, 2004, with Borders Books

u2004.1

In the same year, he repurposed the VDU system at Liverpool St Railway Station in London

(2004.12.1)

adding to the usual security notices, advice about feeling secure - especially in the alienating and lonely environment of an urban train station.

This interest in repurposing information systems coincided with the installation of plasma screens in many public spaces in the UK. For example, Firrell created

A Stronger Self

(2003.1)

for the plasma screen network at Selfridge & Co in London’s Oxford St. Early time-based works like this were created using Adobe’s now defunct Flash software.

NOTE

Adobe Flash was effectively made redundant by the introduction of html5. The Flash Player was discontinued by Adobe at the end of 2020 for all users outside mainland China.

This raises a new set of challenges in relation to the restoration and conservation of digital works like these.

When Caroline Munro unzipped for Lamb’s Navy Rum, she intimated a new way for the artist to engage with sex. Sex in the Lamb’s Navy Rum advertising is not necessarily directed solely at titillation, it is also an invitation to transgression, escape to a life at sea, an entirely other way of being in the world. Sex, Firrell seems to have inferred, could be used to test the edges of moral belief, freedom, and by extension, the health or otherwise of the progressive project.

Early works like

14 Pieces of Erotica for February 14

(2002.5.1-14)

and

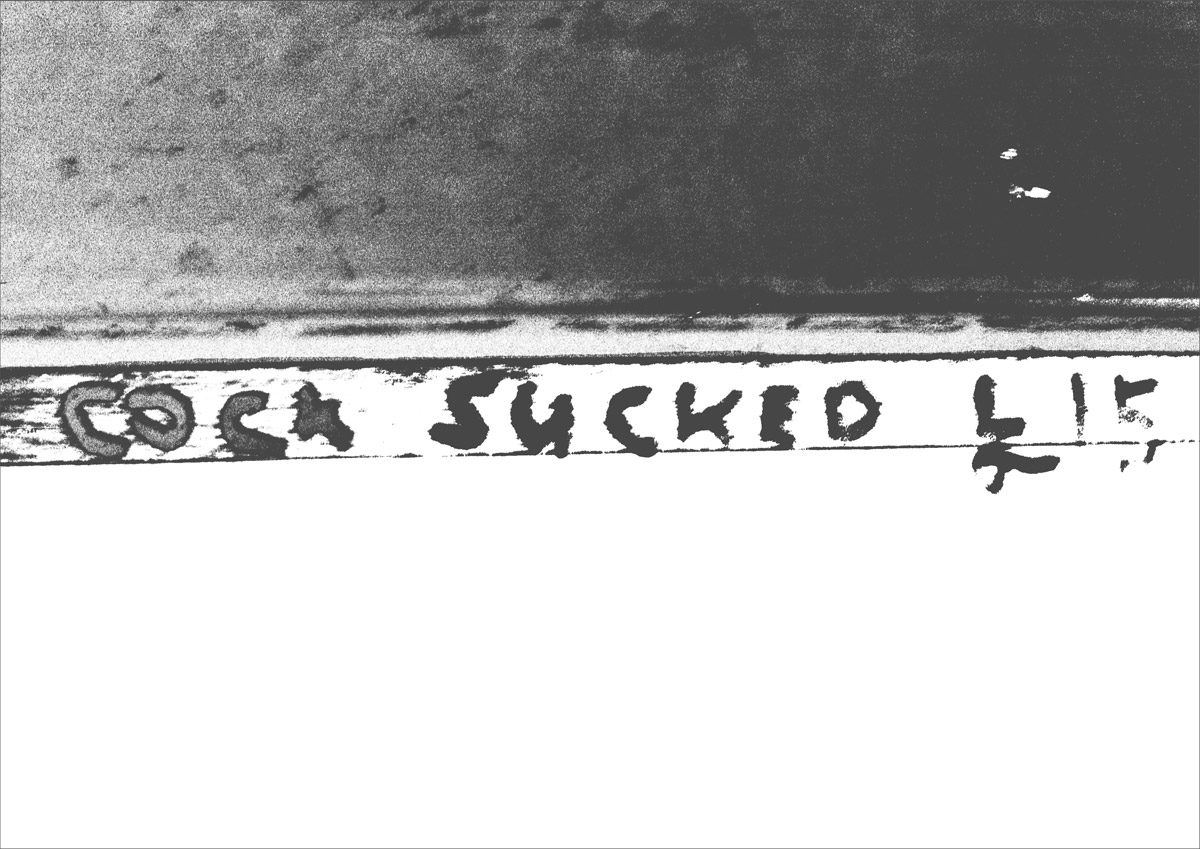

Cock Sucked £15

(2005.1.2)

work in this way, requiring the onlooker to decide where they stand in relation to the status quo and the counteractive liberalising forces that would change or abandon that status quo. The same strategy is utilised in the mature billboard works; in the use of male nudity in the 2020 series

Homosexuals Are Still Revolting

(2020.3.1 - 2020.3.4)

for instance.

Cock Sucked £15, 2005

2005.1.2

Following these early explorations in the public realm, Firrell adopted the commercial billboard as the expressive form central to his public art practice. Over time, the key elements of Firrell’s artmaking in the medium have become easily recognisable. His billboards resemble advertising because they deploy the strategies customarily used by commercial art directors and copywriters (Firrell started his career as an advertising copywriter in 1982). Headlines are bold and short. In later works the typeface is invariably DIN 1451 and headlines are presented in a square block centred in the 48-sheet billboard frame. Noted for its simplicity and clarity, 1451 is the typeface used for German road signs and mirrors the artist’s declarative use of language.

Cod Wars Turned Me Gay

(2022.1.4)

is typical of the artist’s mature work. It looks like advertising. The text dominates the other formal elements, in this case an anonymised trawlerman who acts as illustration to the text rather than a comment on it.

Cod Wars Turned Me Gay, 2022

2022.1.4

The artwork is also paradigmatic in ways which are not immediately obvious. It was created to mark the 50th anniversary year of the UK’s first Gay Pride March in 1972. The artist’s research identified other significant events in the UK in that year including the so called ‘Cod Wars’ - disputes about fishing rights between the UK and Iceland.

Cod Wars Turned Me Gay

tells the true-life story of one teenager's realisation of his gay identity. Scenes on TV of burly trawlermen in conflict over fishing rights triggered a homoerotic awakening. At the same time, the artwork gently satirises the view, prevalent in the early 1970s, that people could 'catch' or 'be turned' LGBT+.

Research has long been an important aspect of the artist’s creative process, especially research into the history of resistance by different minority groups. What is of interest to the artist at a given moment becomes the raw material for the public artwork to come. The research itself is often the source material to be paraphrased, quoted or otherwise reshaped into public art with the power to stir and educate.

The interview form has been equally important. The interview is superior in artistic value to text-based research because the related historical facts are accompanied by the interviewee’s emotional relationship to those facts; history is doubly illuminated by both the interviewee’s knowledge and their feeling.

Many of the artist’s works are rooted in the history of important protest movements.

Embrace Lesbianism and Overthrow the Social Order

(2017.1.1)

has its own immediacy, of course, but it also refers to, and honours, radical lesbian feminism of the 1970s.

Embrace Lesbianism and Overthrow the Social Order, 2017

2017.1.1

As public academic Susan Rudy has noted, ‘The UK’s 1967 Sexual Offences Act partially decriminalised sex between men but made no reference at all to lesbian sex. Lesbian sex had never been taken seriously enough (some even doubted the possibility of it) for society to make laws against it. Consequently this milestone in 'gay' history was not a key moment for gay women - they found themselves undermined, but never outlawed, by the state.’ Firrell goes some way to correcting this original absence by honouring, prominently in public space, the imagination of 1970s lesbian feminists. These women proposed that there were only two ways a woman could genuinely escape male control - the first was to embrace lesbianism as a political position; the second was to overthrow the social order that automatically places men, by virtue of their gender, at the top of the social hierarchy.

The artist, then, co-opts the tropes of commercial art to say non-commercial things. The aim is not necessarily to bring people out onto the streets but to use direct methods to explore the richness and power of the imagination of protest. He is clearly drawn to the ideas, words and images that question the status quo and call for greater social evenhandedness and justice.

‘Politics is not art’ is a charge often levelled at works like Firrell’s. If one accepts that argument, then Delacroix’s

La Liberté guidant le peuple / Liberty Leading the People

must be open to similar criticism. Few people, though, would criticise Delacroix in this way simply because his work belongs to the great tradition of French painting.

There are still people who question whether billboard art can ever really be art. To a degree, this is a ‘skin-deep’ distinction. Whatever has the power to draw the eye, for reasons sufficient to the artist, is art. Where art is implicated in a wider struggle for justice for all, it is bound to be, by definition, political. It is axiomatic and entirely reasonable to agree that not all politics are art, but all art worth the name is, in some way, political.

The artist left advertising in the late 1980s and lived for a while in an apartment on Place Monge in the fifth arrondissement of Paris, not far from the Panthéon. Here the tradition of political discourse and dissent was alive and well. Posters were apprehended as both artform and political instruments following Mai 1968.

In Paris, Firrell encountered the legacy of the great American experimental writer Gertrude Stein.

NOTE

Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) was an American experimental novelist, poet, playwright, art collector and champion of modernism.

Known also as the 'Sybil of Montparnasse' and the 'Mother of Modernism', Stein was a frankly butch lesbian, ‘married’ to Alice B. Toklas,

NOTE

Alice Babette Toklas (1877 – 1967) was an American-born member of the Parisian avant-garde of the early 20th century, and the life partner of American writer Gertrude Stein.

living and working on her own terms absolutely. She cast words in ways that defied all conventions and became Firrell’s magnetic North both professionally and personally.

In his own words:

Stein showed me I wanted to go to war with conformity, with mediocrity, with convention, with ignorance, with compliance, with cruelty. I was caught up in the spirit of the French Republic, the ésprit of Paris, of Liberty Leading the People, of the love of art and culture, and of life itself as an art. Without Stein and without my practice as an artist, I don’t believe my own life would have been possible.

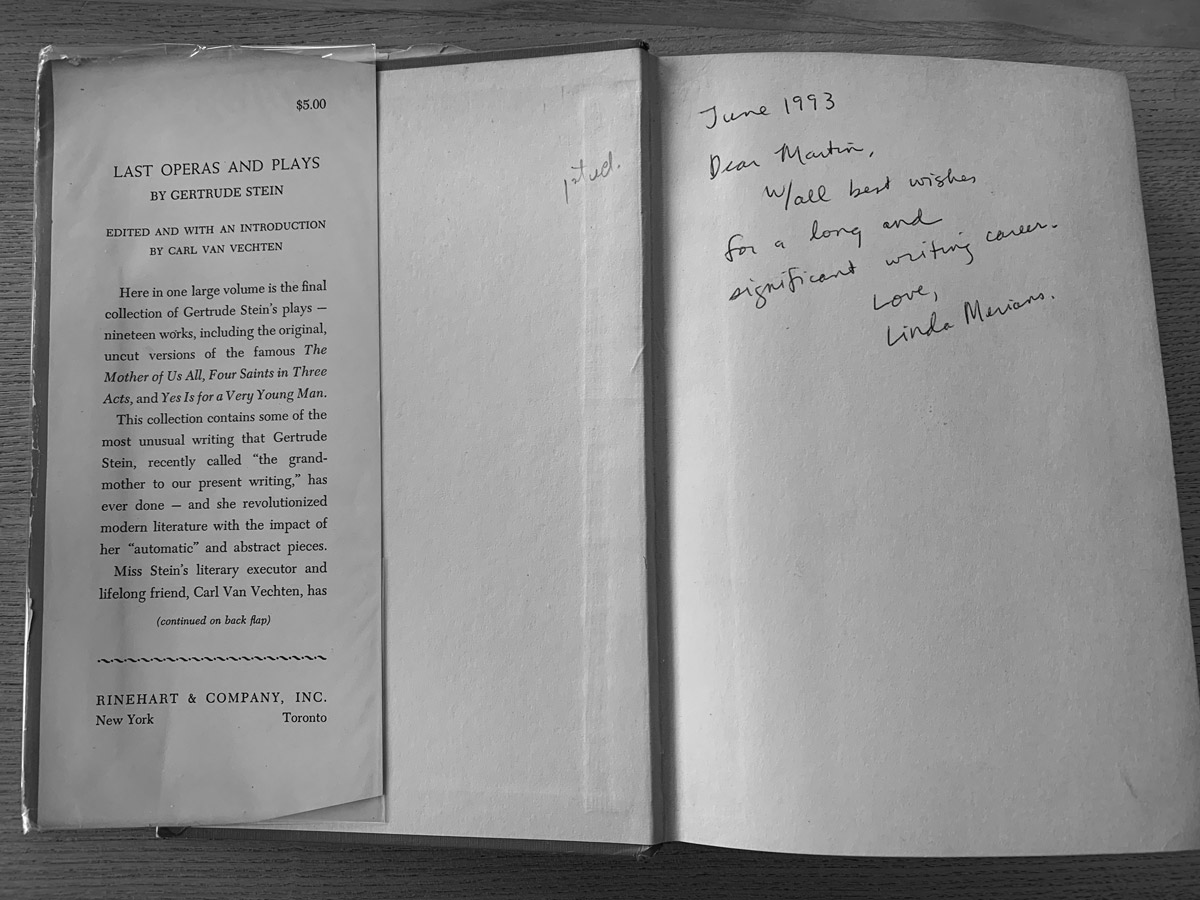

Last Operas and Plays

by Gertrude Stein inscribed to the artist by Professor Linda Merians,1993

b1993.1